by Gillian Ellis

All around the world there are conductors, musicians and musicologists who have the same essential reference book on their shelves.

Orchestral Music: A Handbook is a nuts and bolts guide to the standard repertoire for American orchestra. It lists the duration of each piece, the required instrumentation and the publishers, all assembled and indexed by Oakland University Professor Emeritus

David Daniels, who confesses to a “personality quirk” which leaves him always wanting to “get something just right.”

When he first began conducting regularly, all Daniels had was a list of timings which had been typed for him by his wife

Jimmie Sue. It was a copy of a note book loaned to him by

James Dixon, his mentor at the University of Iowa. Daniels said, “In those days it was not easy to get timings. It wasn't until the CD revolution that timings began to be provided with recordings.”

Professor James Dixon was a protégé of the world-famous conductor

Dimitri Mitropoulos. The two were so close that Dixon had inherited Maestro Mitropoulos’ estate, his scores and royalties. Between the years 1949-1951, Mitropoulos was co-conductor of the New York Philharmonic with the great

Leopold Stokowski, and at this point, we’d like to point out a small circle of coincidence.

Maestro Stokowski conducted the orchestra in the Disney movie

Fantasia. He was shown in dramatic silhouette against brightly colored backdrops. Daniels believes seeing this movie at a very early age was the origin of his conducting ambitions. Referring to the scenes with Stokowski he said, “I had no idea who he was, but it was fascinating. When I was quite young I really wanted to be an orchestral conductor.”

David, who grew up in the small town of Penn Yan, NY, began taking piano lessons at age five. He continued with these but also expanded his skills. He said, “I would spend a couple of years on one orchestral instrument and then a couple of years on the next one, with the result that I can’t play hardly anything very well, but I know how they work, so I can understand their problems if I meet them in the orchestra.” His mother drove him to the Eastman School of Music for piano lessons every week during his high school years, a 100 mile-round trip.

An adult male chorus gave him his first conducting job when he was sixteen, unpaid but a thrilling opportunity nevertheless. “It was quite an experience to be bossing those old men around!”

In high school he was in band, playing saxophone, trumpet, trombone and even bassoon. Outside of school, he played in a jazz combo for which he wrote most of the arrangements. “That was a great practical laboratory,” he said.

He attended Oberlin College, where, to keep up his interest in history and literature, he majored in music in the liberal arts college, rather than entering the famous music conservatory. He says he’s still not sure that was the right decision, but he did enjoy some great experiences, including working with the Gilbert and Sullivan Society, first as their choral director, and later as production conductor. He spent two summers on Cape Cod as choral master of the society’s intensive summer operation. “They did a different G&S operetta every week for six weeks, rehearsing every day for the next week’s opera and doing eight performances a week.” David conducted the matinee performance each week.

Daniels moved on to an M.A. in musicology from Boston University. He said, “It’s been invaluable. Any conductor is going to be a musicologist of sorts.” From there, he took a job teaching music theory and music history at a small college in Missouri, but his desire to conduct never left him. “I composed an opera there so I could have something to conduct,” he said.

Unhappy with his prospects in Missouri, Daniels quit his job without another one to go to. He spent a summer studying at the Tanglewood Music Festival and would return the following year. Through a connection there, he found a new job as a music librarian in Pittsfield, Mass. Three years later, he had skills he knows now have served him well in many ways over the years, but his ambition was still to be an academic orchestral conductor.

Understanding this was probably an impossible dream without a Ph.D., David’s father came to his rescue and offered to finance his son’s studies so he could work on a doctoral degree at the University of Iowa. Jimmie Sue’s parents paid their rent while he studied. “I was so lucky to have this help,” he said, acknowledging that very few parents can offer this kind of support today.

It was at Iowa that he worked with conductor James Dixon, and also with

Gehard Krapf, with whom he studied the organ. David says that he just “hit it off” with both of these men, and Dixon especially remained a mentor to him for many years. He completed an M.F.A. in organ and a Ph.D. in orchestral literature and conducting in 1963.

Daniels held positions at two colleges before arriving at OU in 1969, when the music program was relatively small. But things were about to change. “Those were heady years,” he said. “

Lyle Nordstrom arrived the same year I did and he was a pied piper and a wonderful teacher. He drew all sorts of people into the early music program and many have prospered and gone on to great careers in early music and other things.”

Modestly playing down his own contributions, Daniels also gives credit for the music program’s expansion to tenor

Richard Conrad, who taught at OU for five years and drew many voice students to OU.

David served as the music program’s chair from 1982 to 1988. He recalls this was, “Fun, but extremely draining. . . I would be here until midnight most nights and I got very friendly with the lady who emptied the waste baskets.”

On a more serious note he is quick to say how important the work of

Virginia Ganesky, his former office assistant, was to him. “She was fabulous. That first year I was chair she pushed me around and told me what to do! She was grand.”

David credits his predecessor as chair,

Ray Allvin, with the idea of combining OU’s student orchestra with the Pontiac-Oakland Symphony, a community orchestra. Daniels conducted the resulting orchestra, which recently became the Oakland Symphony Orchestra we know today, for 20 seasons. He believes it was enormously beneficial for the students to work with adult musicians.

Readers may have gathered that Daniels is very quick to recall other people’s work and ideas, but Associate Professor of Music

Greg Cunningham, the current OSO conductor, says that Daniels cannot escape the credit for the Oakland Cooperative Orchestral Library. “David began the library and continues to offer assistance and expertise to maintain and enhance it.”

But David claims that even this was just an accident. The department had three music libraries: Its own, another trove of music scores from the days of the Meadow Brook Summer School and Music Festival, and those bought by Ray Allvin for the Oakland Youth Orchestra. “So we threw them all together and applied library principles.” Gradually, other orchestras sent their music, but even orchestras that chose to keep their own sets in-house entered their data into the catalog and lent them out through the co-op.

Typically, David says that

Rob Burns, who was then a student and now works at Kresge Library, was very influential in putting the catalog together. “Greg gives me too much credit,” he said. “I had the concept but Rob really institutionalized it.”

However, when it comes to his book,

Orchestral Music: A Handbook, Daniels cannot escape the limelight. Greg Cunningham said, “Dr. Daniels has been incredibly influential in the world of orchestral conducting in many ways, but he is most famous for his book. It is an essential reference and people use it all over the world.”

“They do,” said Daniels. “I admit it. I get emails from Australia, Malaysia, Israel, Norway, all over.”

After several years of conducting he began the book as a summer project. As a teacher he was willing to share his knowledge with his students, as his teacher had done before him, but he realized that a book with timings, and more, would be a very useful addition to any music library.

The first edition took him four years to write and was released in 1972, three years after he joined the OU faculty. He is still constantly revising the information, which is now also available on a website. The website is updated every month, with new works added and errors corrected. This massive reference work, which began as a summer project, has become Daniels’ life work.

He retired from OU in 1997, and to honor him the orchestra named the annual young artists concert the “David Daniels Young Artists Concert.” Every year, student musicians, the winners of the department's concerto competition, play with the OSO in their February concert. This is a much sought-after honor and always fiercely contested by the department’s hardest working musicians. They spend many hours of practice perfecting their competition pieces.

The young artists who perform have proved themselves to be people who prefer to “get something just right,” just as David Daniels has always done. The outstanding quality of their work stands as a fitting symbol of the huge legacy he has left Oakland University’s music program.

Orchestral Music: A Handbook is currently available in its fourth edition (2005, Scarecrow Press). A revised fifth edition will be available later in 2015.

The information in

Orchestral Music: A Handbook is available online at the website

orchestralmusic.com which is updated monthly.

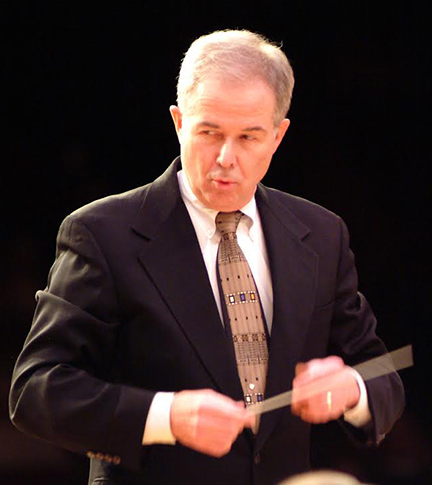

Photos: Top right, David Daniels.

Lower left, David Daniels and tenor Richard Conrad. Photos by Patrick Studio of Warren.

All around the world there are conductors, musicians and musicologists who have the same essential reference book on their shelves. Orchestral Music: A Handbook is a nuts and bolts guide to the standard repertoire for American orchestra. It lists the duration of each piece, the required instrumentation and the publishers, all assembled and indexed by Oakland University Professor Emeritus David Daniels, who confesses to a “personality quirk” which leaves him always wanting to “get something just right.”

All around the world there are conductors, musicians and musicologists who have the same essential reference book on their shelves. Orchestral Music: A Handbook is a nuts and bolts guide to the standard repertoire for American orchestra. It lists the duration of each piece, the required instrumentation and the publishers, all assembled and indexed by Oakland University Professor Emeritus David Daniels, who confesses to a “personality quirk” which leaves him always wanting to “get something just right.” Modestly playing down his own contributions, Daniels also gives credit for the music program’s expansion to tenor Richard Conrad, who taught at OU for five years and drew many voice students to OU.

Modestly playing down his own contributions, Daniels also gives credit for the music program’s expansion to tenor Richard Conrad, who taught at OU for five years and drew many voice students to OU.